Finding agreement and building trust

Conflict in the workplace is so common it’s become a job interview cliché: “Tell me about a time when you had a conflict with [someone on your team | someone on a different team | someone from a different planet].”

As a technical program manager, it’s often my job to resolve conflicts between teams and across functions, but the ability to manage conflicts, to resolve them quickly and productively, is an essential leadership skill regardless of your role or level.

I’ve seen (and caused) my fair share of conflicts, so in this article, I’m going to discuss some strategies for dealing with them.

For context, most of my experience comes from supporting complex software development projects at large technology companies in the US. These projects invariably require individuals and teams to collaborate with and depend on each other.

While I’ve drawn insights and examples from my own career, I hope the ideas here can be applied broadly.

What Is Conflict Management?

Conflict management refers to techniques and strategies for resolving disagreements or arguments between individuals or groups. Ideally, we’d like to resolve conflicts quickly and productively, arriving at a mutually acceptable outcome that improves or at least doesn’t harm the working relationship between the parties.

I prefer the term conflict management over conflict resolution, even though they’re often used interchangeably. Conflict resolution implies that conflict is situational and will be “cured” by the resolution. But conflict never really ends. New conflicts always come up, and old ones that you thought were resolved sometimes resurface. Conflict management better reflects the reality that this is an ongoing activity. It’s part of your job.

Conflict Isn’t Bad

Conflict gets a bad rap. People often think conflict is emotional, hurtful, and leads to lasting animosity. And it can.

But conflict is also an opportunity to be curious, learn, and grow. It can lead to creative problem-solving and innovation.

So, managing conflict respectfully is essential, but avoiding it altogether is neither possible nor desirable.

Causes of Conflict

In my experience, conflicts happen when people disagree about the work they’re supposed to do together and don’t trust each other. In other words:

After all, if people agree, there’s no conflict, and if they trust each other, disagreements, even heated ones, can usually be resolved. It’s when people both disagree and distrust that you get into conflict.

So managing conflict is all about resolving disagreements and building trust.

Disagreements About the Work

When individuals or groups disagree about their work, it’s usually caused by differing approaches, mismatched priorities, or conflicting goals. Let’s take a look at each one.

Different approaches

People often disagree about the approach to doing their work. One person might propose a design that someone else thinks is inefficient or inelegant. One team prefers a specific platform or set of tools that another team doesn’t use.

In my view, this is “good conflict.” You bring people together in front of a whiteboard and hash out the details. You brainstorm ideas. Maybe you discover new possibilities by combining elements of different approaches. Together, you identify the pros and cons of each approach or perhaps compare them in a traffic light analysis.

It’s not always easy; it takes time. Often, you have to go away and gather data, investigate issues, or bring in fresh perspectives from other stakeholders. But in my experience, discussion and debate almost always result in a better solution. Handled well, the process can be fun and rewarding. It’s also a great way to build trust.

However, it does require everyone to remain open-minded and not become emotionally attached to their positions.

Mismatched priorities

People can agree about the approach but still disagree on the importance or priority of the work. I’ve seen priority conflicts arise more times than I can count, usually when one person or team depends on another. On one of my projects, my team needed an additional piece of information from a transaction database to achieve one of our high-priority objectives. It was just one teeny-weeny data point. But the team that owned the database had bigger fish to fry — they were doing a complete redesign — and our “critical” request was just a distraction for them. We waited nearly a year.

No surprise, it’s annoyingly difficult to get others to rearrange their priorities to suit your needs. Here too, though, there’s an opportunity for creative problem-solving.

You can try convincing people to trade off a smaller team goal in favor of a larger organizational goal. To do this, you might need to bring data — sales forecasts, cost/benefit analysis, whatever — to make a case that both teams would benefit from completing the work sooner.

Just be prepared to take the high road yourself when someone asks you to adjust your priorities for the greater good!

Another approach is to jointly figure out ways to reduce the size of the work so it can be done sooner. Perhaps the design can be modified so you or your team can do part of it yourselves, leaving only a smaller piece to be done by others. Maybe you need some minimum level of functionality or completeness right away, while the remainder can wait a little longer. Or you could offer to lend resources to the other group to reduce the size of their effort.

In other words, make it easy for someone to help you. Be reasonable and credible with your requests. Ask only for what you really need and can’t do yourself. Allow plenty of lead time.

Still, priority conflicts can be hard to resolve fully. That’s because they’re often symptoms of the third and most difficult type of disagreement.

Conflicting goals

Goal conflicts occur when two sides disagree over the goals or objectives of the work. They might have different business objectives, be executing different strategies, or be in outright competition. On one project I was supporting a few years ago, my team wanted to reimplement functionality that another team had already built. Of course, we thought we were going to do it better! The other team perceived our efforts as a hostile takeover. The collaboration went nowhere.

You’ll quickly hit a wall with your peers when there are fundamental disagreements about goals or strategies. You might be able to come up with a partial solution or find small areas of agreement, and you should try. But ultimately, you won’t progress until those conflicting goals are resolved.

That means escalating to people higher up the food chain.

Escalating should be your last resort. Resolving conflicts with your partners is best because that helps both sides develop ownership of the solution and trust in each other.

However, there are times when escalation is the right course because you can’t resolve the conflict any other way and because your leaders may be unaware they’ve set conflicting goals.

Escalation moves the conflict to a level in the organization where it can and should be resolved. You’ll have less control over the outcome, but it might be the only way to achieve any outcome.

Building Trust

Disagreement might spark conflict, but distrust is the fuel it feeds on. So let’s talk about trust.

Let me start by acknowledging that there’s a huge body of research and literature about trust, and I’m barely scratching the surface here.

Trust is the foundation of our working relationships. (It’s the foundation of our personal relationships, too, but that’s well outside my scope.)

What is trust? It’s a maddeningly vague concept, but according to one definition, trust is:

“… choosing to risk making something you value vulnerable to another person’s actions.”

— Charles Feltman, The Thin Book of Trust

I like this definition because it highlights that trust involves risk and vulnerability.

When trust is absent, we don’t feel safe taking risks. We feel vulnerable relying on each other. We may feel unsafe sharing our opinions, concerns, or basic information.

Without trust, we are more suspicious and less inclined to give others the benefit of the doubt. We fall back on bureaucratic procedures and paper trails to make up for the lack of trust. When problems crop up, or delays happen, we start questioning each other’s competence, motives, and integrity.

Trust is like engine oil: when it’s present, everything runs smoothly, but when it’s not, they quickly grind to a halt and catch fire.

Trust develops over time

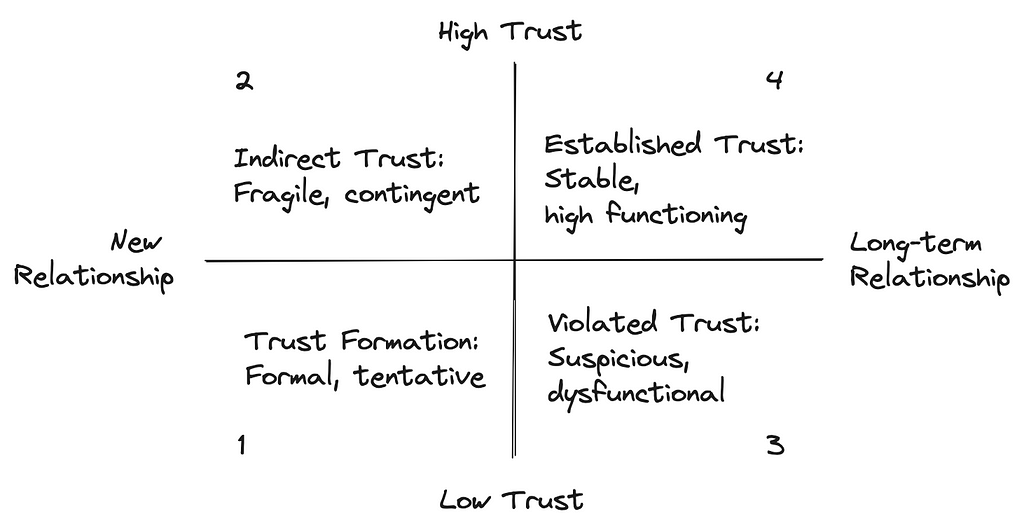

In the diagram below, I’ve tried to show how working relationships vary over time in situations of low and high trust.

In quadrant one at the bottom left, we have newly formed relationships that start off with low trust between the parties. People may rely on formal procedures to bootstrap trust but still feel vulnerable while depending on each other.

In quadrant 2, we see high trust in a new relationship. This is rare but can happen when respected third parties vouch for the reputation or credibility of one or both sides. This kind of trust is indirect. I also think it’s fragile or contingent trust because it hasn’t yet been earned through the direct experience of the people working together. It’s not “battle-tested,” so to speak.

When two parties have been working together for a long time, but trust is still low, as shown in quadrant 3, that’s an indicator trust has been violated in the past. The two sides may be suspicious of each other, and their working relationship is probably dysfunctional. Trust can be violated in many ways, but the most common I’ve seen is when expectations have not been met, or the parties are in direct competition. Repairing violated trust is often more difficult than establishing trust in the first place.

Finally, in quadrant 4, we arrive at a high-functioning state where two people or teams have been working together successfully for some time. They have confidence in each other, willingly take dependencies on each other, share in their successes, and learn from their failures. I’ve been in working relationships like this, and hopefully, you have too because they’re a delight.

How do we get to quadrant 4, the ideal state of established trust?

“Building trust in any relationship takes time because trust is built on a consistent pattern of acting in good faith.”

— Kim Scott, Radical Candor

The key here is consistency. Getting from trust formation in quadrant 1 to established trust can take slow, painstaking work and a commitment to building a long-term relationship. Moving from indirect trust in quadrant 2 to established trust is similar, except you have a small head start, some benefit of the doubt. But you must still earn trust by building a solid track record with the other person or team.

We were in a new relationship with another team in one of my projects. They chose to risk taking a mission-critical dependency on our work. Initially, they imposed strict requirements on how we designed, integrated, and delivered our components. These were quite frustrating and, frankly, slowed us down. Over time, as we proved ourselves capable and achieved some joint successes, we built up enough trust that these constraints were mostly removed.

Recovering from violated trust is the most difficult transition of all. It requires patience, openness, acknowledgement of past mistakes, and a willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

Conflict management strategies

We work with people from diverse backgrounds, origins, and cultures, people with different experiences, perspectives, and abilities than our own. We work with people who have different styles and behaviors than we do.

I think this is one of the great joys of today’s workplace, but these differences mean we need to be thoughtful and deliberate about reaching agreements and building trust.

How do we do this?

There are lots of great articles out there listing many useful conflict management strategies. Most of them can be summed up in three main ideas.

Be curious: Conflicts are an opportunity to learn and be curious. You may need to learn more about the other person or team. So ask lots of questions. Ask about your partner’s goals, motivations, needs, priorities, constraints, and worries. Ask how they like communicating, how frequently, and using what channels. Ask for feedback about how the work is going and how the relationship works.

Personal, cultural, and power differences can influence how we communicate. Give everyone time and space to express themselves in whatever is most comfortable.

Then listen carefully. If you’re not sure, ask for clarification and listen carefully. If you are sure, ask for confirmation and listen carefully.

Be clear: Communicate as clearly and explicitly as possible. Share your own communication preferences. State your and your team’s goals, needs, and constraints. When disagreements occur, highlight them. Use them as an opportunity to problem-solve together and to build trust.

Above all, set clear expectations. People can have different expectations about the scope of the work, the quality of the final product, and the due date for completion. Mismatched expectations are like land mines, hiding just below the surface, waiting to blow up trust. Inevitably they’re discovered just before a big deadline. Avoid this by setting expectations clearly and explicitly. Define “done.” Align early and confirm often.

Be reliable: To reduce the risk of others depending on you, keep your commitments. When you can’t keep them due to unforeseen circumstances, let your partners know as soon as possible so you can work out alternatives or adjustments together.

When you’re asking something of another team or person, make your request reasonable and achievable. Bring supporting data if you can get it. Try to work within your partners’ planning cycles. Don’t expect them to drop everything to meet a last-minute request.

Finally, celebrate wins. Publicly celebrate joint achievements like completion of a project or a milestone or finding the solution to a thorny problem. Share credit. Acknowledge and thank everyone for their contributions on whatever channels are used in your organization.

You can’t prevent all conflict.

You can manage conflict by building trust in your relationships so disagreements can be resolved productively and respectfully.

Thanks for reading.

Conflict Management at Work was originally published in Better Programming on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.